We all know about the life cycle of the caterpillar and its metamorphosis into a butterfly. But did you know that lovely little ladybirds - or ladybugs if you're in the USA - also have a dramatic metamorphosis in their life cycle.

We all know about the life cycle of the caterpillar and its metamorphosis into a butterfly. But did you know that lovely little ladybirds - or ladybugs if you're in the USA - also have a dramatic metamorphosis in their life cycle.

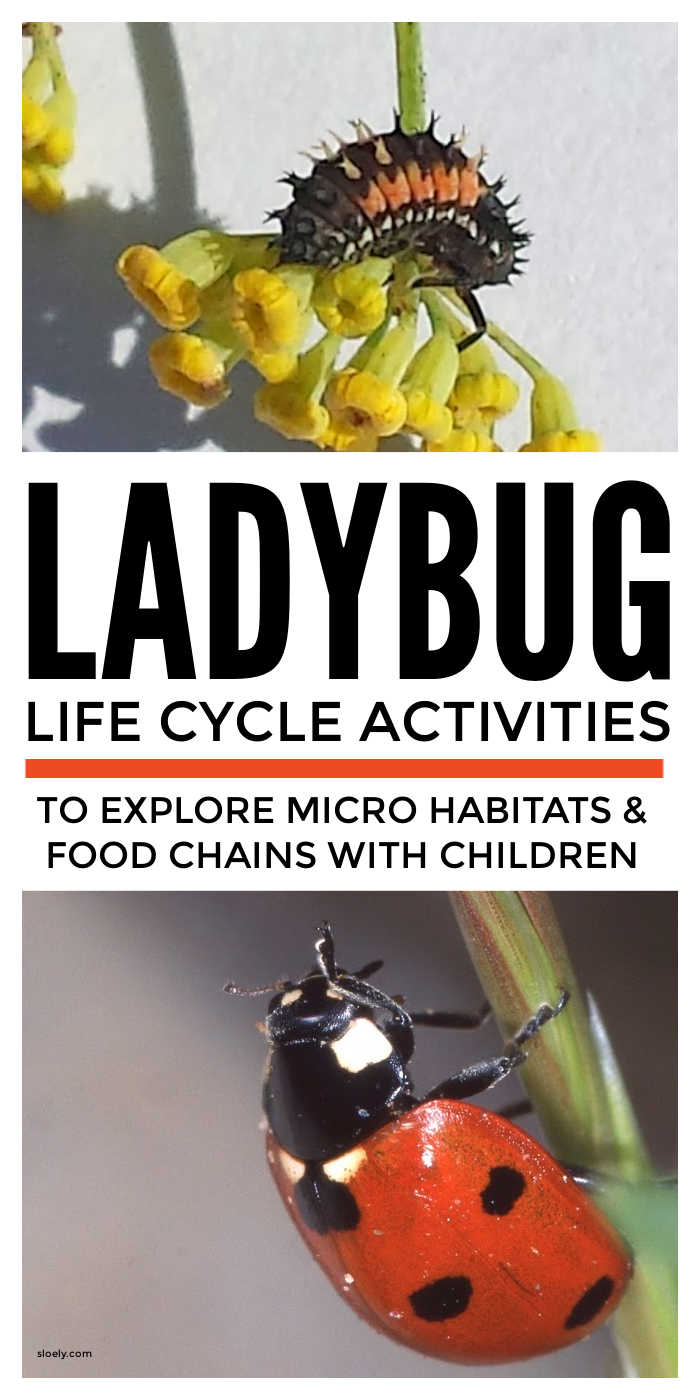

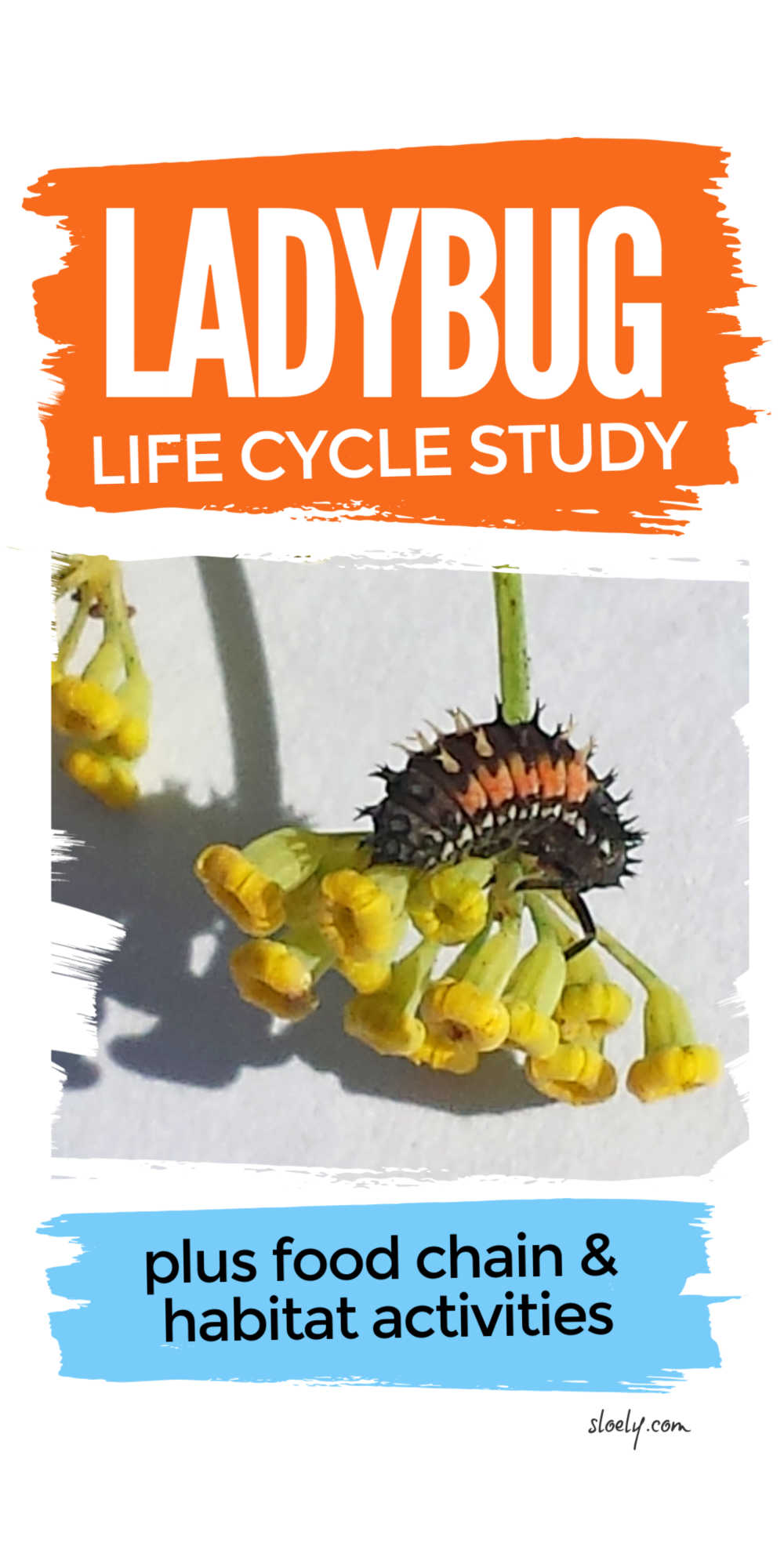

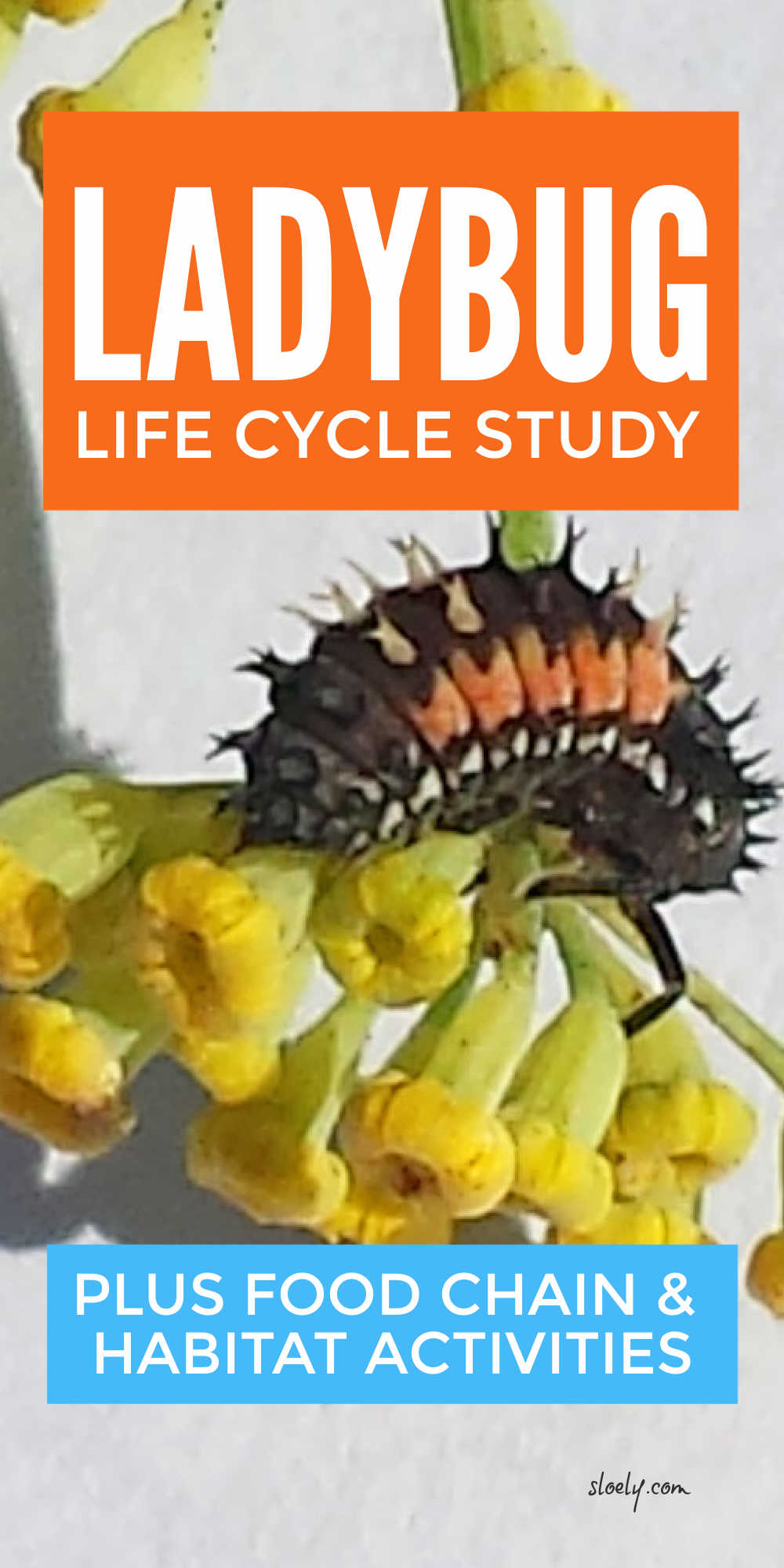

You might not believe it, but that not so pretty little fella in the picture above is actually a baby ladybug or as known properly a Coccinellidae lava.

Who would have guessed?

Ladybirds actually provide the best way for children from preschool and kindergarten through middle school and KS2 to study not only insect life cycles and metamorphosis but also insect food chains and insect habitats.

This is primarily because ladybird populations will establish themselves in a fairly permanent habitat as long as basic food requirements are met.

And by examining ladybugs up close, kids of all ages from preschool to middle school can start to ask themselves the killer question: why on earth do ladybugs - and other insects - go to all that trouble of metamorphosis?

Hopefully this post will help them find out.

I do hope you and your kids or class enjoy getting up close with ladybirds. For more simple hands on nature activities do follow me on Pinterest and check out my other ideas for exploring nature with children.

1. Introduction

In this post I've provided notes on:

- The ladybird lifecycle

- PLUS tips for finding or establishing ladybird habitats

So children can see the ladybug lifecycle, including metamorphosis, in action and observe for themselves the ladybug food chain.

I've included a fair amount of detail in the ladybird life cycle notes that could be used to stretch middle school and KS2 kids but all of the material could be simplified for use with preschool and kindergarten children. The key I think, is not to worry too much about names and labels but to really get kids wondering about why metamorphosis happens.

Thinking about that question helps children to think about the differences in the life cycles of mammals, amphibians and birds as well as insects and to really understand the life process of reproduction.

2. Ladybird Life Cycle

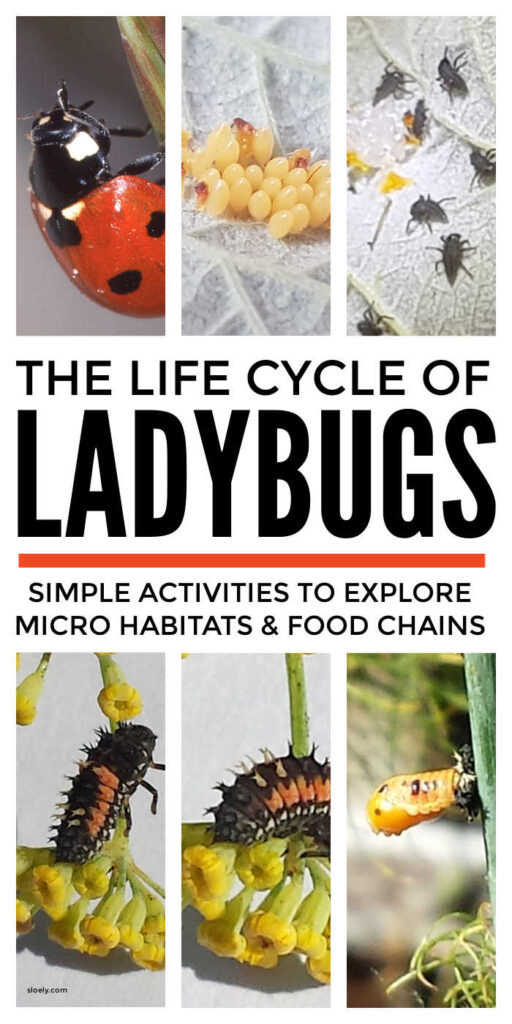

The life cycle of the ladybird - Coccinellidae - includes the same four stages as butterflies and the many other insects who metamorphose.

Ladybird Egg

Females lay 5 to 30 yellow-orange eggs at a time often on the underside of leaves but may lay more than 1,000 eggs in a season. Eggs hatch after 2 to 10 days.

Ladybird Larva

Ladybug larvae emerge from the egg to feed intensely and grow rapidly.

Rapid growth requires them to moult or shed their exoskeleton - or outer body - repeatedly. The period between each moulting is called an instar. Ladybugs typically go through four instars and their markings will change slightly within each.

The ladybug larval stage typically lasts three to four weeks.

Ladybird Pupa

At the end of the larval stage, the ladybug larva attaches itself to a plant and forms a pupa. The ladybug pupa is obtect which means the whole body is enclosed.

In the picture below the ladybird larva has attached itself as a pupa to a plant stem.

Inside the pupa the ladybug larva transforms into an adult. As the ladybird is a holometabolous insect this transformation is an actual metamorphosis which is a pretty gory affair!!!

The ladybug effectively eats itself dissolving most of its cells into a protein rich gloop that can then produce the vast number of new cells needed for the new adult ladybug structure. Wow!!!

This article provides a good description of what's actually going on inside the pupa before the adult ladybird - the imago - emerges.

Ladybird Imago

The adult ladybird emerges from the pupa after one or two weeks.

They now have a new exoskeleton - that hardens into a protective shield after the first few days - complete with wings. And it is the wings that are the key to thinking about that big question we asked at the beginning. Why go through all the hassle of metamorphosis?

Adult insect wings - just like amphibians legs - allow them to travel. So whilst the larva or tadpole stage is all about growing as much as possible as quickly as possible, the adult or imago stage is about leaving home.

Without metamorphosis the ladybird or butterfly or frog will have to breed where it was bred. And that's going to cause a fight for food in the ladybird habitat. Those new wings can fly the ladybird to a whole new colony.

So now lets have a look at ladybird habitats.

3. Ladybird Habitat

There are a number of good places to go looking for ladybirds in your garden or local outdoor spaces:

- Nettles

- Fruit trees and berry bushes

- Large "umbrella" like flowers such as fennel and cow parsley (if you are looking for ladybirds in cow parsley do make sure it is not giant hogsweed as this - I learned the hard way - can cause horrible burns).

You could make finding these - and then hopefully the ladybugs - part of a scavenger hunt.

Nettles are a wonderful micro-habitat for kids to start looking for ladybugs as they are the favourite destination for ladybugs to lay their eggs, nettles being a source of food for the new larvae.

Nettles are a wonderful micro-habitat for kids to start looking for ladybugs as they are the favourite destination for ladybugs to lay their eggs, nettles being a source of food for the new larvae.

Allowing a few nettles to grow in the garden is a wonderful way to create a ladybird friendly habitat.

The older larvae are more likely to be found on the sweet tasting cow parsley or fruit trees and berry bushes. Although ladybirds are omnivores this isn't because they themselves are gorging on the sweet stuff.

They actually move to this new micro-habitat to feed on the various aphids - e.g. green fly and black fly - who do love the sweet stuff. We will talk about the aphids in the next section on the ladybird food chain.

However, we will only find ladybirds in these habitats when the temperature is consistently above 55 degrees fahrenheit or 12 degrees centigrade. When colder than this, the ladybirds go through a period of diapause or hibernation.

Adult ladybirds actually gather together to diapause. They are better able to survive the winter as a group and also use the big meet up as a chance to mate. This stage in the ladybird life cycle is comparable to some bird life cycles such as canada geese, who go to a lot of effort to find their own habitat to reproduce in but then return to a flock for the winter.

These winter groups of ladybirds can get big.

Sometimes they'll number up to a 1,000.

To encourage ladybirds to over winter in a garden build simple log piles of small sticks and moss and old logs. Or build a simple bug hotel.

4. Ladybird Food Chain

Ladybirds may be small - and cute - but they are big - and very useful - predators in the back yard food chain.

Their favourite food as both larva and imago is aphids, the little black, green and white fly that can do so much damage to our plants.

The ladybugs themselves are prey for birds but they do have a clever defence mechanism. Their hardened adult exoskeleton provides some protection but it is actually their bright red colour that really puts off predators as it is associated with poisons.

Curiously, the ladybugs biggest enemy in the garden is not actually somebody in their food chain but the ants.

The ants you see, "milk" aphids of the honeydew they emit from sucking the sweet juices out of plants. The ants actually "herd" the aphids to protect them from the ladybirds and will battle with the ladybirds to defend those pesky flies they so depend upon.

So on your scavenger hunt around the garden or park to find ladybugs in their natural habitat do look out not only for the aphids but also for large armies of ants with whom the ladybirds are at war!!

And there you go.

All sorts of super cool stuff about ladybug life cycles, habitats and food chains that kids can actually get up close and look for in their own backyard.

I do hope you enjoyed this post for more simple ideas for exploring nature with kids do follow me on Pinterest and have a read of these posts with lots more ideas for exploring nature with children :

- How Bees See To Pollinate Flowers

- Growing Plants With Males & Female Flowers

- Plant Life Cycles : The Chestnut Tree

- Dissecting Flowers To Explore Pollination

Leave a Reply